![]() A few months ago, Yoctopuce launched a color sensor based on the spectral analysis of light. This module not only provides raw measures, but it also estimates the color of the object that produced the measured spectrum. As there is no mathematical formula directly applicable to this task, this feature has required a fair amount of experimentation to verify the reliability of the obtained results. Today, we present one of the test methods we used.

A few months ago, Yoctopuce launched a color sensor based on the spectral analysis of light. This module not only provides raw measures, but it also estimates the color of the object that produced the measured spectrum. As there is no mathematical formula directly applicable to this task, this feature has required a fair amount of experimentation to verify the reliability of the obtained results. Today, we present one of the test methods we used.

Color sensors

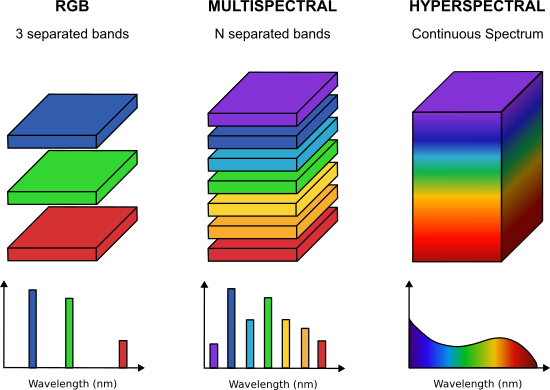

The apparent color of an object depends on the spectrum of visible frequencies it reflects in contact with ambient light. There are three main color sensor technologies:

Differences between RGB, multispectral, and hyperspectral sensors

The most trivial method is based on the use of an RGB sensor, which measures light intensity specifically in three well-defined frequency bands: red, green, and blue. It's based on the observation that the human eye sees colors using cones sensitive to red, green, and blue, and that focusing on these three frequency bands could therefore be enough to recognize all colors. Unfortunately, this approach is too simplistic to be reliable: it overlooks the fact that the cones of the human eye have a very broad band, and that we cannot therefore go directly from measuring intensity in three narrow bands to describing a color by its RGB coordinates.

In contrast, there are hyperspectral sensors capable of providing a quantitative measure of energy over dozens or even hundreds of frequency bands, covering the entire visible spectrum. This exhaustive approach enables extremely precise color characterization. Unfortunately, hyperspectral sensors are complex and expensive scientific instruments.

In between, multispectral sensors, such as the Yocto-Spectral, measure reflected light at a dozen or so wavelengths, spread across the entire visible spectrum. This spectral signature is then transformed into coordinates in a color space, using a predictive model trained on a corpus of a few hundred measures taken on calibrated color cards.

To check that the predictive model is working properly, we then run experiments to see whether new measures, under different conditions, still produce the right results. As these experiments are by nature repetitive, it's interesting - and much more fun - to automate them. Here's one in particular that we like.

Color sorting experiment

In this experiment, the Yocto-Spectral is used to sort color cards from the RAL palette, classifying them according to 11 basic colors: brown, red, orange, yellow, white, gray, black, green, blue, purple, and pink. Sorting is performed automatically using a UFactory uArm Swift Pro mechanical arm.

Color sorting, 5 times accelerated sequence

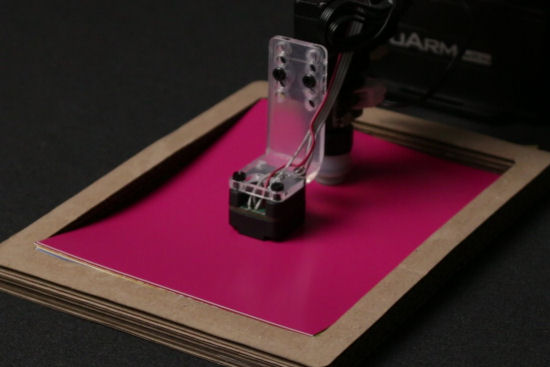

To measure the color of the card at the end of the arm, we removed the measuring part of the Yocto-Spectral as indicated in the user's guide, and attached it to the end of the mechanical arm using the Spectral-Adapter, attached to a bracket. This bracket allows the sensor to be positioned at the same height as the arm's suction cup, which is used to move the color sheets.

Yocto-Spectral remote sensor fitted with adapter

Once the system is in place, all the sheets are stacked in the center of the table. The mechanical arm then moves to pick up the top sheet, while pressing the sheet under the sensor. The Yocto-Spectral estimates the color of the sheet's surface and compares the result with the 11 basic colors to assign the sheet to the corresponding stack. The mechanical arm then moves the sheet to the location dedicated to the recognized color, and the process is repeated for each sheet in the stack.

Color sorting process

This small system enabled us to test the operation of the color classification algorithm in real-life conditions, to validate processing speed, and to verify repeatability and tolerance to variations in illumination conditions.

Sheets sorted by color